The RBI AIF exposure cap introduced in July 2025 marks a significant shift in how banks and NBFCs can invest in Alternative Investment Funds. The new framework places clear limits on exposure, provisioning, and capital treatment, making AIF investments subject to tighter regulatory scrutiny.

On 29 July 2025, the Reserve Bank of India introduced a clear RBI AIF exposure cap for regulated entities. Under this framework, a single bank or NBFC cannot invest more than 10% in an AIF scheme. In addition, the combined exposure of all regulated entities cannot exceed 20% of the scheme’s total corpus.

As a result, AIF investments will now face tighter regulatory scrutiny.

More importantly, certain structures will trigger higher provisioning and capital impact.

These directions come into effect from 1 January 2026. However, regulated entities may adopt them earlier based on internal policies. Through this move, RBI aims to reduce concentration risk, improve transparency, and prevent indirect exposure build-up.

The New Guidelines at a Glance

To begin with, the RBI circular introduces four major changes.

Individual Cap: 10%

First, a single regulated entity cannot contribute more than 10% of the corpus of an AIF scheme. This rule prevents excessive dependence on one bank or NBFC.

Collective Cap: 20%

Second, the total contribution of all regulated entities combined cannot exceed 20% of an AIF scheme’s corpus. Consequently, AIFs must diversify their investor base beyond regulated institutions.

Downstream Investment Provisioning

Third, the RBI tightens rules around downstream investments.

If a regulated entity contributes more than 5% to an AIF scheme, and that scheme invests (excluding equity instruments) in a company that is already the entity’s debtor, the entity must make 100% provision on its proportionate exposure. This provisioning applies up to the level of the entity’s direct exposure.

Subordinated Units and Capital Deduction

Finally, the RBI revises the treatment of subordinated units.

When a regulated entity invests in an AIF through subordinated units, it must deduct the entire investment from its capital funds, proportionately across Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital where applicable.

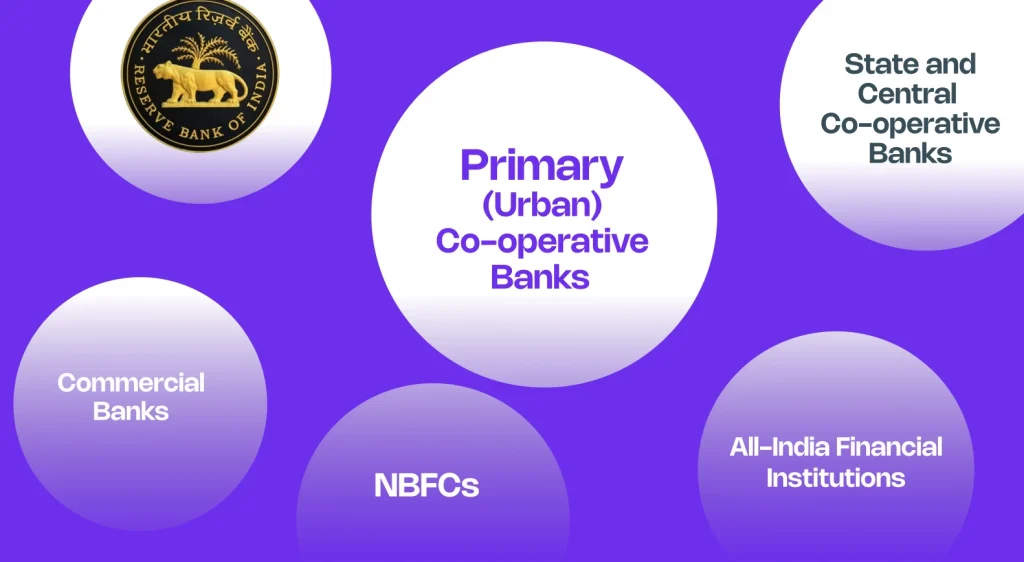

Entities Covered Under These Directions

These guidelines apply to:

- Commercial Banks, including Small Finance Banks, Local Area Banks, and Regional Rural Banks

- Primary (Urban) Co-operative Banks

- State and Central Co-operative Banks

- All-India Financial Institutions

- NBFCs, including Housing Finance Companies

Therefore, any regulated entity with AIF exposure must reassess both portfolio strategy and compliance controls.

Why the RBI Introduced These Guidelines

At its core, the RBI introduced these rules to strengthen risk management.

Over time, regulators observed the misuse of the AIF route for loan evergreening. In several cases, banks and NBFCs indirectly funded stressed borrowers through AIF structures. As a result, institutions delayed provisioning and avoided asset quality downgrades.

This practice reduced transparency.

More importantly, it concealed actual credit risk.

Therefore, RBI introduced the 10% individual cap to limit concentration risk. At the same time, the 20% collective cap ensures that AIF schemes do not function as extensions of regulated balance sheets.

In short, the regulator wants AIFs to remain diversified investment vehicles rather than tools for regulatory arbitrage.

Provisioning and Capital Treatment: The Fine Print

One of the most impactful aspects of the circular relates to provisioning.

If a regulated entity holds more than 5% of an AIF scheme, and the AIF invests in an existing debtor of that entity, the entity must make 100% provision on its proportionate exposure. This requirement directly addresses attempts to bypass IRAC norms through indirect lending.

As a result, overlapping exposure between direct loans and AIF investments becomes significantly more expensive.

Similarly, subordinated unit investments now attract strict capital treatment. Since these units rank lower in liquidation waterfalls, RBI requires full capital deduction. Consequently, capital adequacy ratios may take an immediate hit.

Together, these measures discourage indirect lending structures and promote cleaner balance-sheet reporting.

Implications for Regulated Entities

For banks and NBFCs, this circular marks a strategic turning point.

Previously, AIFs offered flexibility, diversification, and higher yields. However, the revised guidelines reduce the scope for concentrated or complex exposure structures.

As a result, regulated entities can expect the following changes:

- Tighter Internal Compliance: Institutions must actively monitor AIF exposure to avoid breaching caps.

- Reduction in Concentrated Bets: Large allocations to single AIF schemes will require rebalancing.

- Capital Recalibration: Subordinated unit investments now directly affect capital adequacy.

- Provisioning Impact: Downstream overlap with existing debtors can materially affect earnings.

Consequently, many institutions will initiate internal risk reviews, portfolio restructuring, and capital planning exercises.

Implications for AIFs and Fund Managers

From the perspective of AIFs, the circular may reshape fundraising dynamics.

Historically, banks and NBFCs formed a significant investor base, especially for Category II and III debt-oriented funds. However, the new limits restrict how much capital regulated entities can provide.

As a result, fund managers may need to:

- Diversify fundraising toward HNIs, family offices, and non-regulated institutions

- Strengthen governance and disclosure around downstream investments

- Adopt more conservative lending strategies when regulated investors exceed 5% exposure

Over time, this shift may improve transparency and alignment with both RBI and SEBI expectations.

Alignment with SEBI and the End of Arbitrage

Another important outcome is regulatory alignment.

The revised RBI framework brings AIF-related exposure norms closer to SEBI’s due diligence and risk assessment standards. Consequently, the scope for regulatory arbitrage through layered structures reduces significantly.

By closing this gap, regulators reinforce consistent risk discipline across India’s financial system.

The Bottom Line

The RBI AIF exposure cap introduced in July 2025 represents a decisive step toward stronger financial stability. By limiting both individual and collective exposure, RBI reinforces the principle that risk-taking must align with transparency and capital discipline.

From 2026 onward, banks and NBFCs will need to treat AIF investments as strategic exposures rather than yield-driven allocations. At the same time, fund managers must adapt to diversified investor pools and tighter governance expectations.

In an environment where compliance is no longer optional, these guidelines set the tone for a more resilient and responsible investment ecosystem.

At BeFiSc, we help financial institutions and asset managers stay ahead of evolving regulations through compliance-driven APIs and intelligent risk infrastructure. From onboarding and entity checks to ongoing risk monitoring, our tools support regulator-aligned AIF operations.

FAQ

What is the RBI AIF exposure cap for banks and NBFCs?

The RBI AIF exposure cap limits a single regulated entity to 10% of an AIF scheme’s corpus. It also caps the combined exposure of all regulated entities at 20% of the scheme’s total corpus.

When do the RBI AIF exposure cap rules come into effect?

The rules take effect from 1 January 2026. However, banks and NBFCs may implement them earlier based on internal policy decisions.

What happens if an AIF invests in a company that is already a debtor of the bank or NBFC?

If a regulated entity contributes more than 5% to an AIF and the AIF makes downstream investments (excluding equity) in an existing debtor, the entity must make 100% provisioning on its proportionate exposure, subject to RBI limits.

Why does RBI require capital deduction for subordinated unit investments?

RBI requires full capital deduction for subordinated units because they carry a higher loss risk. This ensures that capital adequacy ratios reflect the true risk of indirect exposures through AIFs.